There is no question that mass shooting incidents in this country are unfortunately continuing at a staggering pace.

As of April 29, the crowd-sourced “Mass Shooting Tracker” project, which considers a mass shooting to include a single incident in which four or more people are shot in any incident, lists 163 incidents that fit this criterion for 2024.[1] That number marks an ominous beginning to 2024.

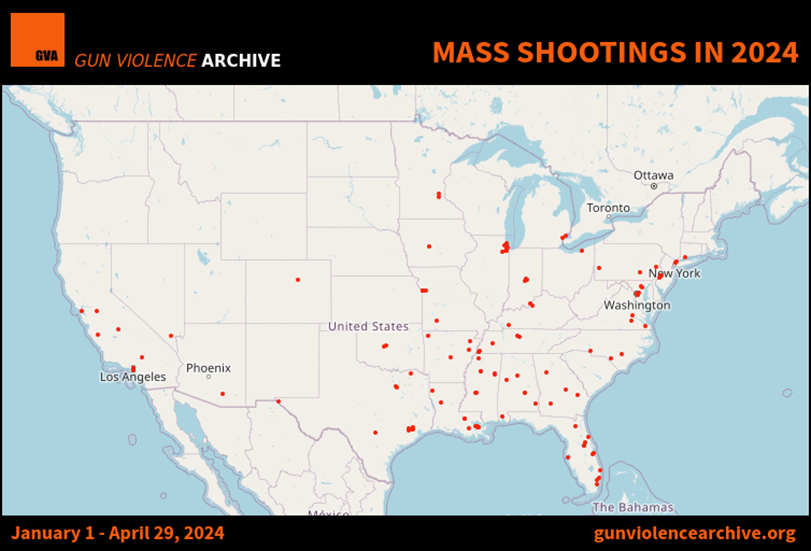

Moreover, as illustrated by the chart below prepared by https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/, mass shootings are not limited to a specific geographical area.

Aside from the human tragedy that mass shootings invoke, the practical reality of each mass shooting is that in addition to a potential criminal prosecution, a civil action against actors other than the alleged perpetrator is virtually certain to follow.

Targets of such civil actions have included, among others, hospitality companies, landlords, security firms, property management firms and public entities. An active plaintiffs bar has targeted such parties under negligence-based theories and recovered settlements routinely in the seven figures, if not higher.

What may fly under the radar, however, is that the insurance industry is often called upon to fund the defense and settlement of those civil actions. Most frequently, policyholders seek coverage for those civil actions under their commercial general liability policies.

In this article, I assume that the claim noticed by the policyholder involves a covered occurrence, coverage is not barred by an exclusion and the policyholder does not maintain an active-shooter insurance policy. I focus on how the number of occurrences is judicially determined for a mass shooting incident under a commercial general liability policy.[2]

The most recent pronouncement on the occurrence issue was made on March 20 by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida on pending cross-motions for summary judgment in the long-standing litigation, Tony v. Evanston Insurance Co.[3]

The Tony litigation stems from the Feb. 14, 2018, Parkland High School mass shooting. Following this horrific incident, multiple lawsuits were filed against the Broward County Sheriff’s Office, or BSO, and others by the shooting victims and their families.

The lawsuits generally allege that the BSO, including its agent Scott Peterson — the school resource officer on duty at the high school to protect teachers and students from threats, including those posed by the active shooter, Nikolas Cruz — were negligent in, among other things, failing to follow the BSO’s own practices and procedures.[4]

The lawsuits further allege that, but for this negligence, the shootings would not have taken place, or at the very least, some of the deaths and injuries would have been prevented.[5]

Following early motion practice, the case moved to discovery, and, on Jan. 12, both sides cross-moved for summary judgment.[6]

On its summary judgment motion, the BSO argued that it was entitled to summary judgment because (1) the court had already held during earlier motion practice that the term “occurrence” within the meaning of the public entity insurance policy at issue was ambiguous, as it reasonably could be interpreted to mean either the entire shooting spree by Cruz or each shot he fired that resulted in separate injuries to a separate victim; and (2) due to this ambiguity, the Parkland High School mass shooting incident must be construed as a single occurrence under the policy, subject to one $500,000 self-insured retention.[7]

On its motion, the insurer argued that it was entitled to summary judgment because (1) there is no ambiguity in the term “occurrence” and the allegations of the mass shooting incident constitute more than one occurrence, (2) the BOS had not demonstrated that it paid its annual aggregate deductible, and (3) the Florida rule of contract construction that ambiguities must be construed in favor of the policyholder is not applicable to the BSO, as a sophisticated entity.[8]

The court granted the BSO’s motion and denied the insurer’s motion. Specifically, the court refused to reverse its prior rulings in the case and maintained that the term “occurrence” was ambiguous.[9] Therefore, the court held that the mass shooting involved only one occurrence subject to one single $500,000 self-insured retention.

Additionally, the court rejected the insurer’s contention that the Florida rule of contract construction that ambiguities must be construed in favor of the policyholder was applicable to the BSO, since the insurer did not establish that the BSO drafted or prepared the definition of “occurrence” supplied in the policy.[10]

Notably, the court in Tony did not apply Florida’s construction of the cause standard applied in 2003 by the Florida Supreme Court in Koikos v. Travelers Insurance Co.[11]

In Koikos, the Florida Supreme Court held that injuries sustained by two individuals who were shot in a restaurant lobby constituted separate occurrences.[12] The policy defined “occurrence” as “an accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to substantially the same general harmful conditions.”[13]

The court concluded that, notwithstanding that the insured restaurant owner was sued for negligent failure to provide security, “occurrence” is defined by the immediate injury-producing act and not by the underlying tortious omission.[14]

Stated differently, under the Koikos court’s theory, each round fired that caused injury was considered an occurrence as the immediate act giving rise to the injury.[15]

The Tony court explained that the cause theory was not applied because the “term ‘occurrence’ within the meaning of the Policy is ambiguous as applied to the facts in this case, as it reasonably can be interpreted to mean either the entire shooting spree by Cruz or each shot he fired that resulted in separate injuries to a separate victim.”[16]

Given that ambiguities in policy language are construed in the policyholder’s favor, and because the BSO favored the Parkland shooting incident to be a single occurrence under the policy since it meant that the BSO only needed to satisfy one self-insured retention, that is the interpretation the Tony court adopted.[17]

On April 18, Evanston Insurance Co. filed a notice of appeal of the Tony court’s summary judgment decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit. As such, it remains to be seen whether the 11th Circuit will sustain the district court’s decision.

Separately, it should be noted that Florida’s application of the cause theory is not followed by most jurisdictions that have addressed the number of occurrences implicated by a mass shooting event.[18]

For example, in Donegal Mutual Insurance Co. v. Baumhammers, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court held in 2007 that, under the cause theory, to determine the number of occurrences, courts look to the cause or causes of the damage.[19]

In Donegal, the Pennsylvania court distinguished Koikos and applied the cause theory to find that substantially similar facts gave rise to one occurrence.

Specifically, the insurer in Donegal issued a homeowner’s policy to the parents of the shooter, an adult resident of the household.[20] On April 28, 2000, the shooter left his home and shot and killed his neighbor. He then drove to two other towns and killed four other individuals.[21]

The shooter’s parents were sued for negligence for failing to take the gun, or alert police or mental health professionals about the shooter’s dangerous propensities, which constituted an accident under Pennsylvania law.[22]

Using the cause approach, the Pennsylvania court held that under such an approach, the “more appropriate application of the cause approach is to focus on the act of the insured[s] that gave rise to their liability.”[23]

The court explained that determining the number of occurrences by looking to the underlying negligence of the policyholder recognizes that the question of the extent of coverage rests upon the contractual obligation of the insurer to the policyholder.[24]

Accordingly, the court concluded that while the case was “disturbing … with tragic consequences, … [it was] compelled to conclude that Parents’ alleged negligence constituted but a single ‘occurrence.'”[25]

In sum, the Tony summary judgment decision reinforces that the determination of the number of occurrences is critical to both policyholders and insurers alike when determining how much coverage is available to respond to a mass shooting claim.

Sophisticated predictive modeling techniques used by some insurers — those that insure hospitality venues, schools and other public venues — may help analyze potential risks and their severity. But such technology can only mitigate; it cannot obviate the risk of a mass shooting.

Unfortunately, it is evident that mass shooting events will continue to occur, and so questions of coverage, and the occurrence question in particular, will continue to be perennial issues for insurers and policyholders.[26]